Do estimated breeding values work?

You will remember that phenotype depends upon both genetics and environment:

P = G + E

When you're looking at hip scores, or at one descended testicle, or an x-ray of dysplastic elbows, or the MRI of a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel suspected to have syringomyelia, you are assessing phenotype only. You have no idea how much of the variation you see from animal to animal for your trait of interest is attributable to genetics and how much to environment. Because selection can only operate on genetics, knowing the true genetic value for a trait in a particular dog is extremely EBVs they have been proven to be of great value in the artificial selection of particular traits in livestock and other domestic animals.

"But", you say, "dogs aren't livestock". Can EBVs be used successfully in dogs?

Here are a couple of examples. You will see that in both, the efforts of breeders to control a genetic problem had little success before the adoption of EBVs.

Historically, Boxers have had a high incidence of cryptorchidism (one or both testicles fail to descend). If neither testicle descends the dog will be sterile (the heat of the body interferes with sperm production), but a dog with one testicle is fertile although prone to testicular tumors. Apparently, most living Boxers can trace their pedigrees to four German stud dogs - Sigurd von Dom and his three grandsons, Utz von Dom, Dorian von Marienhof, and Lustig von Dom. All four of these dogs produced cryptorchid offspring.

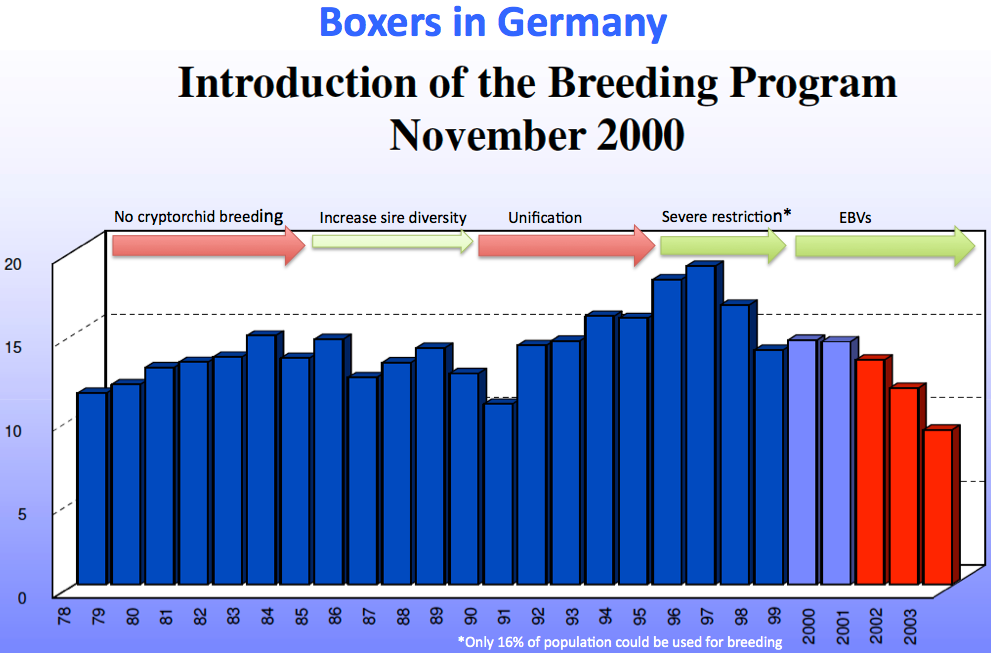

First efforts to reduce the frequency of cryptorchidism in Boxer began in 1942, with a total ban on breeding cryptorchids. Nevertheless, the incidence of cryptorchidism increased over the next 40 years from about 6% in 1941 to 10% in 1981in East German dogs. In West Germany, it increased from 7% in 1959 to 14% in 1985. In 1985, concerns about genetic diversity in the breed prompted encouragement to breeders to breed to lesser known males, but this did not improve the incidence of cryptorchidism. The unification of Germany in 1984 improved access to a broader gene pool, but cryptorchidism increases unabated for the next 10 years. In 1996, once again strict regulations on breeding were imposed, excluding a bitch from breeding if she produced cryptorchid offspring in 2 litters, and eliminating sires with more than 15% cryptorchids in at least 20 offspring. These measures reduced the frequency of cryptorchids, but it also removed 84% of the reproductive dogs from the breeding pool and improvement tailed off after a few years.

Finally in 2000, Germany removed all restrictions related to cryptorchidism and instituted the use of estimated breeding values (EBVs) to improve selection against cryptorchidism. Within only 3 years they saw marked improvement. This information is from a report published in 2003; more recent information is not available, but it would be very interesting to see if there was continued improvement or if cryptorchidism was at least reduced to a tolerable level.

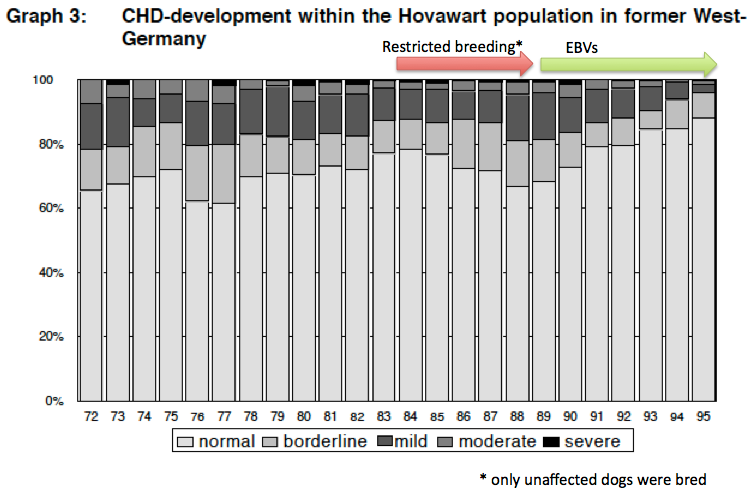

EBVs have been use for some time to reduce the frequency of canine hip dysplasia (CHD) in many breeds. These are data from a breeding program against CHD in the Hovawart. Again, because selection against phenotype failed to produce consistent improvement for several decades, severe breeding restrictions were instituted in 1984 that banned all affected dogs from breeding. This actually made things worse, reducing the number of unaffected dogs and increasing the number of dogs classed as borderline.

In 1989, selection based on EBVs was instituted, and this produced immediate, significant improvement in hip scores, and in only 5 years more than 80% of all dogs had normal hips and severely afflicted animals were nearly eliminated.

These are dramatic examples of the improvements that can be achieved in just a few years by using EBVs to guide selection instead of phenotype. EBVs also breeders to distinguish between, for example, dogs with bad hips and dogs with the genes for bad hips - essentially separating the potential influence of environment from the underlying genotype that the breeder is really interested in. This means that fewer animals will get removed from the gene pool, because dogs with a bad phenotype but good genotype for the trait of interest can be kept in the breeding stock for potential use.

Using EBVs for selection can produce one problem that is common to phenotypic selection as well. If everybody rushes to the dog with the best EBV score, this will increase inbreeding if care is not taken to balance the reproduction of animals across the breadth of the gene pool. This should be a basic part of sound genetic management of a breeding population of animals anyway, regardless of the scheme breeders are using to make breeding decisions.

EBVs will be new to many dog breeders, but in fact they have been used for decades to guide breeding decisions of service dogs. Using EBVs, a well-run organization can manage genetic disorders, limit inbreeding, and produce dogs with the traits that are important in a service dog, even in a closed gene pool. This improves the efficiency the breeding program because more of the dogs produced are suitable for service.

Dog breeders can used EBVs to dramatically improve their ability to improve the traits they want and reduce or even eliminate the ones they don't. EBVs can be used on any trait that can be evaluated by the breeder - temperament, size, herding ability, coat quality, heart disease, "showiness", hip dysplasia - anything you can judge to be better or worse, desirable or not desirable. EBVs are becoming available in more and more countries, and they are the most powerful tool now available for improving the health and well being of dogs.

Reading in Nicholas: Ch 15, Selection within populations- p. 235-248; Ch 21, Genetic and environmental control of inherited disorders- p. 300-301.

This is more detail than we get into here, because you'll never have to do the calculations yourself, but it is good to understand what is behind them.